Parameterizing Linq Query Selectors

Recently I had the requirement for a typical query method that should return a special object out of a kind of repository.

To give the child a name, say we have a customer repository and we need to get a customer based on its customer number that would be a string. Thus, the method’s signature would look like this:

Customer GetCustomer(string customerNo)

Fair enough, that looks like the obvious routine stuff: query the underlying storage of customers to get the matching customer - nice and easy with linq:

Customer GetCustomer(string customerNo)

{

...

return _customers.Single(c => c.CustomerNo == customerNo);

...

}

What If We Cannot Find A Customer?

It’s getting a bit more interesting if we think of the case where we cannot find a customer for the given customer number.

Option 1: Throw An Exception

In the implementation above, we would throw an InvalidOperationException because the predicate c => c.CustomerNo == customerNo would evaluate to false for each and every customer.

That is just one possible behavior.

Option 2: Return null

One alternative would be to return null. To reach that, we just need to change the call to the extension method Single to SingleOrDefault:

Customer GetCustomer(string customerNo)

{

...

return _customers.SingleOrDefault(c => c.CustomerNo == customerNo);

...

}

(In the context of this discussion, I will leave out other options such as returning some kind of NullObject or Maybe<Customer>)

For me, choosing between those two options has not always been an easy decision. At worst it came that I mixed both approaches, resulting in an inconsistent and unpredictable api.

Convention Xy() and XyOrDefault()

In recent years, being accustomed to the goodness and style of the System.Linq namespace, instead of choosing between one of the two option mentioned above, I would provide a pair of method, each implementing one of these options.

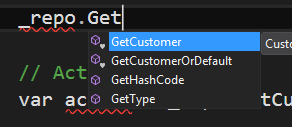

There would be a method GetCustomer that throws an exception if it cannot find a proper object, and another method GetCustomerOrDefault that would return null in that case.

Taking advantage of intellisense, it should be obvious for the user of the api which method to choose based on the needs of the calling code:

Implementation

Assuming that we are perfectly happy with a InvalidOperationException in the case of GetCustomer, we might end up with this pair of methods:

Customer GetCustomer(string customerNo)

{

...

return _customers.Single(c => c.CustomerNo == customerNo);

...

}

Customer GetCustomerOrDefault(string customerNo)

{

...

return _customers.SingleOrDefault(c => c.CustomerNo == customerNo);

...

}

Looking at this sample we could consider this task done and move on.

Some Reality

But if we consider a more realistic situation, i.e. that the ellipses hides a considerable amount of cruft, such as context/session handling or logging ceremony, and that the predicate would not be that simple, the whole story could rather look like this:

Customer GetCustomer(string customerNo)

{

using (var session = new SqlServerSession(_connectionString))

{

_logger.LogInformation(string.Format("Querying customer repository by customerNo \"{0}\", customerNo));

return Db(session).Customers

.Select(c => new ExternalCustomer(c))

.Single(c => c.CustomerNo == customerNo &&

c.IsActive);

}

}

Customer GetCustomerOrDefault(string customerNo)

{

using (var session = new SqlServerSession(_connectionString))

{

_logger.LogInformation(string.Format("Querying customer repository by customerNo \"{0}\", customerNo));

return Db(session).Customers

.Select(c => new ExternalCustomer(c))

.SingleOrDefault(c => c.CustomerNo == customerNo &&

c.IsActive);

}

}

Now these two methods cry out loud Copy/Paste Programming!!!, and Violating DRY!!! so that we urgently need to do something about it.

Parameterizing Single(...) / SingleOrDefault(...)

Still assuming that we are perfectly fine with the behavior of those two methods (what could be argued about), we will want to find a way to somehow pass the single thing that is different between those methods: the call to Single(), and the call to SingleOrDefault(), resp.

One easy way would be to refactor this code like this:

Customer GetCustomer(string customerNo)

{

return GetCustomers.Single(c => c.CustomerNo == customerNo &&

c.IsActive);

}

Customer GetCustomerOrDefault(string customerNo)

{

return GetCustomers.SingleOrDefault(c => c.CustomerNo == customerNo &&

c.IsActive);

}

private IQueryable<Customer> GetCustomers()

{

using (var session = new SqlServerSession(_connectionString))

{

_logger.LogInformation(string.Format("Querying customer repository by customerNo \"{0}\", customerNo));

return Db(session).Customers

.Select(c => new ExternalCustomer(c));

}

}

In this example most of the cruft is kept in a single place. Unfortunately, we are still left with the duplicated predicate, provoking subtle bugs if the query logic has to be changed later on.

Wouldn’t it be nice to pass in just the function, and leave all the logic in the method GetCustomers?

We can do this using a Func parameter. This parameter has to repeat the signature of the methods Single and SingleOrDefault:

// From System.Linq.Enumerable

public static TSource Single<TSource>(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource, bool> predicate);

If we want to pass a delegate like this around, the delegate has to be of the following type:

Func<IEnumerable<T>, Func<T, bool>, T>

For those not yet familiar with the Func-syntax, this denotes a delegate with two input parameters and a return value:

IEnumerable<T>: A enumerable sequence of some typeFunc<T, bool>: A predicate. That is a function that takes an object and returns a Boolean

The last type parameter T defines the return value of the delegate being of the same type as the elements in the sequence of the first parameter.

Putting It All Together

Bringing that to life, we get the following code (again leaving out the awful things by now):

Customer GetCustomer(string customerNo)

{

return GetCustomers((list, pred) => list.Single(pred));

}

Customer GetCustomerOrDefault(string customerNo)

{

return GetCustomers((list, pred) => list.SingleOrDefault(pred));

}

private IQueryable<Customer> GetCustomers(Func<IEnumerable<T>> sequence, Func<T, bool>, T> selFunc)

{

...

return selFunc(_customers, c => c.CustomerNo == customerNo);

...

}

We now have gained that all the magic code and logic in its entirety is kept in method GetCustomers. The two callers just vary the distinctive parts.

Getting Rid Of The Syntactic Clutter

Although we have already come a long way, there is still some repetition in the two callers - the syntactic clutter from the two-parameters lambda expressions.

Pausing For A Moment

As you might know - or your productivity addin such as ReSharper tells you from time to time - there are cases where it is possible to get rid of this arrow syntax.

To analyze such a case, consider this example:

class Foo

{

...

void DoSomething()

{

... someList.Select(item => CanUse(item));

}

...

bool CanUse(Item item) { ... }

...

}

Here we can get rid of the lambda syntax by just using the name of the method that is called in the lambda expression:

class Foo

{

...

void DoSomething()

{

... someList.Select(CanUse);

}

...

bool CanUse(Item item) { ... }

...

}

Why Our Case Looks Different

Back to our example, we do not directly have the opportunity for the short-hand syntax. Also in our case, the lambda-expression is solely made of a single method call. But that method is not a member of the calling class, but a member of one of the parameters.

Compare

... someList.Select(item => CanUse(item));

from the recent example to

return GetCustomers((list, pred) => list.SingleOrDefault(pred));

from our original code.

Are We Lost?

No. At that point we just have to think one step further:

The methods used with Linq such as Single or SingleOrDefault are brought to the scene in form of extension methods defined in the static class System.Linq.Enumerable. We can confirm this by going back to the declaration of the method Single as we have already seen above:

// From System.Linq.Enumerable

public static TSource Single<TSource>(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource, bool> predicate);

From this signature we see that the native call to Single could be

... = Enumerable.Single(list, predicate);

But the enhancement of the first parameter with the keyword this makes it an extension method, allowing for the familiar invocation with the syntax of a member method of the sequence:

... = list.Single(predicate);

Understanding that, we can inverse this thought process and write our methods GetCustomer and GetCustomerOrDefault like this:

Customer GetCustomer(string customerNo)

{

return GetCustomers((list, pred) => Enumerable.Single(list, pred));

}

Customer GetCustomerOrDefault(string customerNo)

{

return GetCustomers((list, pred) => Enumerable.SingleOrDefault(list, pred));

}

...

But That’s Even More To Type!

We now have the situation where we can use the nice short-hand syntax without the explicit lambda expression:

Customer GetCustomer(string customerNo)

{

return GetCustomers(Enumerable.Single);

}

Customer GetCustomerOrDefault(string customerNo)

{

return GetCustomers(Enumerable.SingleOrDefault);

}

...

Now That’s Neat!

At the end of our travel, we have found the simplest method possible to just pass the minimum distinguishable code.

Nice, isn’t it?