The Case Of The NullReferenceException

As most developers, you might not be happy if a piece of software you wrote throws an exception.

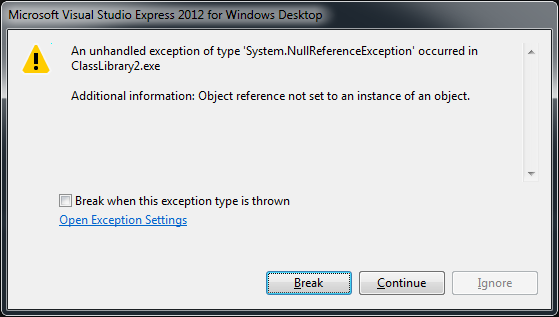

TODO: Screenshot of exception in Visual Studio

An uncaught exception makes it obvious that there is something wrong, something has to be fixed.

Assuming a reproducible failure condition, the case falls basically into two areas: either your code has a severe bug, or some component is just not called properly.

In either case,

The exception is your friend

It tells you explicitly, that there is something left to do.

If something is wrong in our system, we should be more than happy to hear about it. Unmistakably and fast. We will not want to be left in a false sense of happiness until the failure condition causes a maybe much bigger problem downstream.

TODO: Image of a NullReferenceException

Subtitle: Infamous Quote From A StackTrace: “Object Instance Not Set To An Instance Of An Object”

An all too well known sign of missing to fail fast is the occurrence of a NullReferenceException.

Although it might be super-obvious to you, let us discuss in some detail how we might end at a NullReferenceException.

Reasons For A NullReferenceException

First we will recap some very basic stuff here to get us all on the same page.

Say we have a class Person with a property Name. A typical usage could look like this:

var me = new Person();

me.Name = "Paul";

Everything is easy and cozy. In the line me.Name = "Paul"; we assign a value to the name of the object me.

But what is me?

me represents an object of type Person. The important thing is to be clear that me is not a person object by itself. Rather it is a reference to a person object.

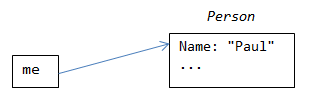

In a simple fashion, we can think of this little image:

There is a thing call me pointing to another thing that is a Person having a name equal to "Paul". In more technical terms there is an object variable me referencing an instance of class Person with a value "Paul" for the property Name.

For the following discussion let us deconstruct the first line of our little code snippet from above to see the different parts:

Person me = new Person();

(To make things more ovious, the variable is now declared explicitly.)

We can dissect this innocent line in the three parts declaration, allocation, and assignment.

We will now go to each of those in more detail.

1. Declaration

The left part of the statement means: We need a place to store a reference to an object of type Person and want to give it the name me:

Person me ...

In the image above, this is just the little box:

If you have the feeling, that something import is missing, you might be right. But hold on for a minute. We will come back to the issue later.

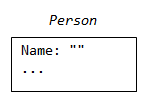

2. Allocation

The right part of the statement means: We need a new object of type Person:

... new Person()

Note that at this point, the object is in its initial state. For property Name we want to assume that this is just an empty string:

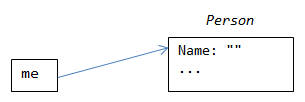

3. Assignment

The connecting part of the former two is the assignment operator:

... = ...

This one sets the reference denoted with me to point to the new object of type Person:

(Up to now, we’ve left out the semicolon as the last non-whitespace character from the complete statement. For our purpose we consider it a syntactical necessity to conclude the statement.)

The Real Thing

As you might have noticed, in my description and image of the part “1. Declaration”, I have left out one vital thing: Where does a reference like me point to, if it is not part of an assignment of any kind? While a new operator without assignment or member call is not feasible on its own, a lonesome variable declaration is perfectly fine:

Person me;

Just after that declaration alone, the reference of me cannot be queried - it is undefined. Every access to it other than an assignment will result in a compilation error:

Person me;

var x = me; // Error: Use of unassigned local variable 'me'

me.Name = "Paul"; // Error: Use of unassigned local variable 'me'

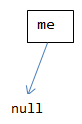

But what can we do if we know we need a variable later on, but are not ready to let it reference a concrete object? As we know, we might assign it to null:

Person me = null;

var x = me; // Compiles fine

me.Name = "Paul"; // Compiles fine (but at runtime ...)

We can imagine this situation as a reference pointing to a commonly well known place for any reference variable, that has nothing to reference to:

If we run the code above, in the attempt to assign the value "Paul" to the property Name we get our beloved NullReferenceException:

The NullReferenceException tells us that there is something missing. Maybe it means that some object could not be found in a dictionary because of a wrong value for the key on lookup.

The real problem is that the message of the NullReferenceException tells us exactly nothing more. If we are lucky, what might help is the StackTrace. Poor us if that very line the top of StackTrace points to contains several candidates as in the following example:

var data = x.GetData(y.Name, z);

In this line of code the reason for the NullReferenceException can be x or y being null. So you can guess. z cannot be the candidate because in common it is perfectly fine to pass a null as a method parameter. If the NullReferenceException occurs in the method GetData(), the top of the stacktrace would not be the very line above.

That problem obviously occurs on the attempt to access a member of a reference variable that is null.

Guard Clause

The best would be to avoid surprises on member access. In common that means putting a check for each of those variables before the first member access happens. This is sometimes called a guard clause:

if (x == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException("x");

TODO Show a ArgumentNullException at runtime

In the sense of failing early, we will want to add the guard clause as early as possible: on entry of a method or on beginning of a class, at construction.

- If the member access of the method parameter happens unconditionally, then the guard clause can be done right on top of the method body.

- If the reference in question is a passed as constructor parameter, this constructor is the first place where you can check if the parameter is not null.

Let us see one example for each of these situations.

Guard Clause For Method Parameter

Let’s assume that our Person class keeps track of the person’s addresses. For some reason we want to provide a method that returns all cities that are used in the addresses of the person.

The following code fragment illustrates this:

public class Person

{

private readonly IList<Address> _addresses;

...

public AddAddress(Address address)

{

_addresses.Add(address);

}

...

public IList<City> GetCities()

{

return _addresses.Distinct(a => a.City).ToList();

}

...

}

Once bitten, it is not difficult to see the spot for a NullReferenceException: it is the lambda-expression in GetCities. If any of the references in _addresses is null, a call to GetCities will throw a NullReferenceException. Therefore it is not feasible to even allow a null reference to be added to _addresses.

The only way to completely hinder this situation is to put a guard clause in front of the call to Add in method AddAddress, resulting in

public AddAddress(Address address)

{

if (address == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException("address");

_addresses.Add(address);

}

With this little trick we can be sure that no null will be in _addresses.

Guard Clause For Constructor Parameter

Let us now consider another incarnation of the class Person, where each person has a single Address:

public class Person

{

private readonly Address _address;

public Person(Address address)

{

_address = address;

}

...

public override string ToString()

{

return Name + " (" + _address.City + ")";

}

}

From looking at method ToString we see that passing a non-null reference of Address is crucial, otherwise ToString would crash the program since it unconditionally access the City property.

In this situation, the constructor is the proper place to put a guard clause:

public class Person

{

private readonly Address _address;

public Person(Address address)

{

if (address == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException("address");

_address = address;

}

...

public override string ToString()

{

return Name + " (" + _address.City + ")";

}

}

With that in place we can be sure that each instance of Person has a non-null Address.